Kidney stones are pretty common. Over 2 million people suffer from kidney stones each year in the USA alone. Put another way, up to 3% of the general population develop kidney stones each year. Kidney stones are not just a feature of modern living - physicians like Hippocrates who saw patients in the BC era looked after patients with kidney stones. So having had centuries to figure out what kidney stones are, what have we learned?

Mind Your Language

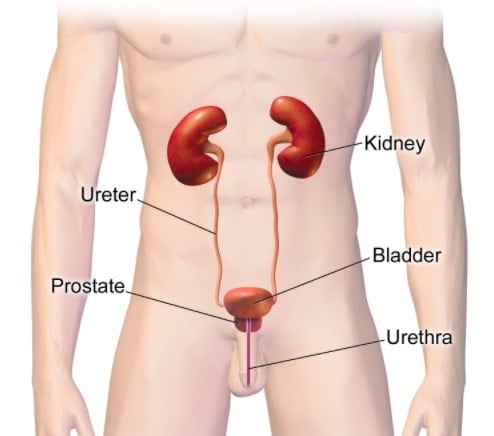

The language of kidney stones can be confusing. Let’s start at the beginning. Most people have two kidneys. The kidneys are connected to the bladder by long tubes called ureters. Stones can form anywhere from the kidneys to the bladder.

If the stones are in the kidney, the terms nephrolithiasis, kidney stones, renal stones, renal calculi are used.

If the stones are in the ureter, the term ureterolithiasis is used.

Bladder stones are called vesical calculi or cystolith.

In common parlance, the term 'kidney stone' is usually used to refer to stones anywhere in the urinary tract.

Classification System

Stones are classified by:

- Size

- Location and

- Composition (uric acid, cystine, magnesium).

Two types of stones deserve an extra special mention.

Struvite Stones

Bacteria in the urine can release ammonia ions which combine with magnesium and calcium to form stones known as struvite stones. These stones are less amenable to medical management and may need surgical intervention.

Staghorn Calculus

These stones occupy prime real estate at the junction between the kidney and the ureter. They are more often made of struvite, larger and can be branched in shape. Again they are more likely to need surgical intervention.

Who Gets Kidney Stones?

We know that 2 million people per year develop kidney stones. The question is who are these two million people (aka what are the risk factors for kidney stones)?

Kidney stones are more common in:

- men

- whites

- older age

- hot climates

- decreased fluid intake

- medications eg acetazolamide, indinavir

- high dietary oxalate eg rhubarb.

White men have a 12% lifetime risk of developing kidney stones.

How do Renal Stones Present?

Many people with kidney stones have no symptoms at all. The stones are diagnosed as "incidentalomas" - meaning that they have a scan done for some other reason and kidney stones are noted.

The presence/absence of symptoms depends on the ratio of the size of the stone to the location of the stone ie a small stone in the widest part of the ureter may not cause any symptoms while a large stone in the narrowest part of the ureter can cause a sudden onset of very severe pain.

Women compare the pain of kidney stones to the pain of labor. That is a pretty strong validation of the potential severity of pain of kidney stones. I have never heard women compare migraine pain or period pain to the pain of labor. Kidney stones, you have our respect and attention. This comparison makes sense actually, as both labor and kidney stones involve trying to force a relatively large object (baby or stone) though a small space. Quite a feat.

Many people also complain of nausea and vomiting.

The classic finding on examination is finding extreme tenderness in the loins (I mean Iike patients yelp).

Patients with kidney are usually writhing around with the pain, desperately trying to find a comfortable position. (Top insider secret here- there is no comfortable position). This is one of the ways that we distinguish appendicitis or ectopic pregnancy from renal stones. People with appendicitis and ectopic pregnancy are in significant pain but they tend not to want to move as it makes their pain even worse.

This is not an absolute science, but just clinical clues.

So how do we move from clinical clues to a confirmed diagnosis?

How are Renal Stones Diagnosed?

Patients with kidney stones usually undergo a battery of tests including blood work and urine analysis. These tests give useful additional information but do not actually clinch the diagnosis. The diagnosis is made by radiological imaging which shows the actual stones. This can be plain x-ray, ultrasound, CT scan. Different scans are better at diagnosing different types of stones eg regular ultrasound is almost blind to stones in the ureter and plain x-ray is not great at uric acid stones.

Complications

This all depends on the size and location of the stone.

A large stone relative to a narrow ureter can prevent the flow of urine. Apart from the fact that this causes pain, it can also cause kidney failure, infection in the backlogged urine, abscess around the kidney, narrowing of the ureter and/or sepsis.

Is There any Research?

There are almost 25, 000 studies on renal stones including 1000 clinical trials. To put this into context, gallstones have 18,000 publications and 800 clinical trials.

Two of the key groups who design guidelines for the management of renal stones are the American Urological Association and the European Association of Urology (1, 2).

Management of Renal Stones

This again all depends on the famous ratio of the stone to the space that it is occupying.

As mentioned above, many people have no symptoms and may not need any management.

Stones less than 4mm in diameter are likely to just pass spontaneously.

Stones greater than 10mm in diameter are unlikely to pass spontaneously.

The management of renal stones is divided into medical and surgical options.

- Medical Management

The aim of medical management is symptom relief, management of possible complications, prevention of increase in size of the existing stone, prevention of new stone formation and facilitation of passage of the stone. - Intravenous Rehydration

Symptom Control - Pain relief & anti-nausea medications - Antibiotics

Citrate (an organic acid found in citric fruits) - Surgical Management

Up to 20% of stones need to be removed surgically. As mentioned above, surgical intervention is usually required for larger stones that are less likely to pass spontaneously. Staghorn stones and stones made of struvite are also more likely to need surgical removal.

Surgical options include:

Shock wave lithotripsy therapy: this is where sound waves break up stones into smaller pieces which can then be passed in the urine. High energy shock waves are produced by an electrical discharge which is then targeted on the stone with the aid of fluoroscopic imaging.

Ureteroscopy or Retrograde Intrarenal Surgery where a tube is passed into the ureter from the outside (yes the penis in men) and is threaded up through the ureter. Yes, we put you asleep for this.

Nephrolithotomy where the surgeon removes the stone via the abdomen either by a more traditional incision or keyhole surgery. Open stone surgery is only used in 1% of people.

What Does The Research Say?

I have exercised my literary privilege here and chosen a selection of papers from among the 25,000 publications papers that I thought were either interesting or informative relating to renal stone management.

I have exercised my literary privilege here and chosen a selection of papers from among the 25,000 publications papers that I thought were either interesting or informative relating to renal stone management.

My definition of "interesting" is something that I did not know, find quirky or contradicts the treatment guidelines.

One of the most interesting pieces of research on renal stones that I came across shows a possible association between renal stones and heart disease in women (3). This 2014 study from China analyzed data from 49,597 patients with kidney stones and 3,558,053 controls, with 133,589 cardiovascular events.

There was a statistically significant increase in the risk of heart disease and stroke in women with renal stones but not in men. As we know that women, in general, have a lower risk of renal stones than men, is there a possibility that women with renal stones are not representative of women in general? I am not sure but it is interesting.

Another interesting meta-analysis from Thailand and the USA found that there may be an association between bariatric surgery and renal stones (4). Pooled analysis from over 10,000 patients showed an association between certain types of bariatric surgery and renal stones (roux-en-Y). The popular banding bariatric surgery was shown to decrease the risks of renal stones.

Chinese investigators addressed a fundamental belief in the management of renal stones - fluid intake (5).

Fluid intake is thought to play two roles in renal stones:

- Fluid replacement to reverse dehydration caused by vomiting or reduced oral intake

- Facilitation of passage of the stone.

Let's focus on the role of hydration in flushing out stones. I am pretty sure that if I got on any bus in Dublin and told the random person next to me that I had a kidney stone that I would be told to 'drink lots to flush it out'. These Chinese investigators asked if this is an urban myth or a proven scientific fact. Drum roll, please.

Technically, no study met the inclusion criteria set out by the Chinese investigators. One study of 199 patients showed that increased water intake reduces the risk of recurrence of urinary stones and prolongs the average interval for recurrences. Intuitively, it makes sense that extra fluid might help. Why is there not lots of proof supporting this?

I guess there are two possibilities here:

- It is actually an urban myth

- It is just too "obvious" and has not been properly researched.

A 2015 Scottish systematic review and meta-analysis which compared the clinical effectiveness of shock wave lithotripsy, retrograde intrarenal surgery, and percutaneous nephrolithotomy for lower-pole renal stones parsed data from 2741 records; 7 randomized controlled trials and 691 patients (6). Overall, the review found that percutaneous nephrolithotomy and retrograde intrarenal surgery were superior to shock wave lithotripsy in clearing the stones within 3 months.

Citrate is frequently used and recommended in the management of renal stones. It is used both in prevention and treatment. The theoretical rationale for using citrate goes as follows. Low urinary citrate levels are associated with high rates of calcium stones. Oral citrate treatment increases urinary citrate levels. The increased urinary citrate binds to calcium and prevents stone formation.

A comprehensive meta-analysis found 7 studies with 477 participants on citrate in renal stones found that citrate significantly reduced stone formation and stone size (7). Even better, citrate was well tolerated. That would be very interesting but the problem is that the data was moderate to poor quality.

A 2017 systematic review and meta-analysis from Colombia looked at options for pain relief for renal stones and found that diclofenac was superior to paracetamol and other NSAIDS (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs). Paracetamol was also superior to opiates (8). That is a hard sell to patients who are writhing around in pain.

Italian investigators did a meta-analysis and looked at the role of herbal medicines in the treatment of kidney stones (9). Initially, they found 541 articles but whittled this down to only 16 eligible and informative articles.

They found that citrate and a herbal combination preparation containing Didymocarpus pedicellata (a herb used in traditional Indian medicine) were significantly better than placebo at clearing stones.

A study published last year looked at drugs to help with medical expulsion of stones (10).

Another study was conducted by Indian investigators and looked at 120 patients who were given either tamsulosin or silodosin or silodosin plus tadalafil. Say what now? Let me explain. It is pretty interesting actually.

The ureter is an essentially long tube. This tube has receptors that can help move stones along towards the bladder. The presence of stones interrupts the normal functioning of this tube. Just the very time that we need the tube to work at warp speed. Murphys Law.

Drugs known as alpha-blockers (tamsulosin and silodosin) can help the ureter to dilate and contract rhythmically. Drugs known as phosphodiesterase inhibitors (sildenafil (Viagra) and tadalafil) can also help relax the ureter. Theoretically, alpha-blockers and/or phosphodiesterase inhibitors could help expel stones in the ureters. But does the theory translate into action? The answer, yes. The expulsion rate of in the silodosin plus tadalafil arm was statistically superior to the other arms and it was also statistically better in terms of pain control.

Another study that addresses an important question is whether calcium supplementation increases the risk of kidney stones? Given that some kidney stones are made of calcium, this is a reasonable question and concern. Spanish investigators looked at data from 10 trails involving mostly middle-aged women who were taking calcium supplements for bone health (11).

Only 21 of the 8000 women developed kidney stones which were not considered to be above the rate that would be expected in any population. The authors concluded that calcium supplementation of up to 1500mg for three years did not increase the risk of kidney stones.

Having looked at the issue of calcium, I then turned my attention to vitamin D. I found an interesting article which was a Chinese study published in 2016 (12). Fast forward two years and the 2016 article was withdrawn by the team due to methodological issues. I find it really interesting to think of all of the layers of bureaucracy (aka reviews) that this paper slipped by and no one noticed the methodological issues.

Luckily, investigators from New Zealand came to the recuse with another review (13). Data from almost 20,000 people showed no connection between vitamin D levels or supplementation and renal stones. The study also validated the lack of a connection between calcium and renal stones.

Conclusions

Considering how common kidney stones are and the fact that they date back to the BC era, there is surprisingly little depth in the medical or surgical literature on this topic. Can I just say that instrumentation of the urethra (yes, the penis in men) to access stones (even if it does work) seems like basic plumbing belonging to the Roman empire and not part of 21st century modern medicine?

Leave a Reply