Table of Contents

What Is Cryotherapy?

The term “cryotherapy” comes from the Greek terms “cryo,” meaning cold, and “therapy,” meaning cure. Cryotherapy is defined as cooling the body for therapeutic purposes, primarily to reduce pain and inflammation. Cryotherapy can be applied using various methods, including the use of ice packs, ice towels, ice massages, frozen peas, gel packs, vapo-coolant sprays, ice immersion, and a cold whirlpool bath.1

In general, cryotherapy is administered to relieve pain and inflammatory symptoms caused by numerous disorders, particularly those associated with rheumatic conditions. It has been recommended for the treatment of arthritis, fibromyalgia, and ankylosing spondylitis, and has more recently been used by athletes to relieve muscle soreness after exercise.

Cryotherapy can be broadly categorized into:

a) whole-body cryotherapy (WBC) and

b) partial-body cryotherapy (PBC).

WBC involves exposing a patient’s entire body to extremely cold, dry air at sub-zero temperatures (below −100 °C or −73 °F) in a cryochamber (via liquid nitrogen and refrigerated cold air) in a controlled clinical environment for two to four minutes.

During this exposure, the patient wears minimal clothing, gloves, a woolen headband covering the ears, a nose and mouth mask, and dry shoes and socks. PBC treatment, on the other hand, is performed in a partial cryocabin called a cryosauna, which is an open tank that exposes the patient to cold temperatures by spraying nitrogen directed at the body (excluding the head and neck).

In recent years, the use of WBC has gained popularity among athletes as a form of therapy to relieve muscle soreness after exercise. Proponents of cryotherapy advocate that it not only alleviates muscle and joint pain, but it also promotes weight loss, has anti-ageing benefits, can relieve anxiety and depression, and can improve sleep. Due to these claims of everyday health benefits, cryotherapy has also gained popularity among non-athletes and is provided at “health” clinics at exorbitant prices.

Immersing oneself into a freezing chamber sounds to me like something out of a sci-fi movie; therefore, I wanted to find out why WBC has become so popular and examine the validity of its supposed health benefits.

This article focuses on the use of Whole-Body Cryotherapy for the benefits of improved health.

Brief History of Cryotherapy

The Egyptians used cold to treat injuries and inflammation as early as 2500 BC.2 Between 1845 and 1851, Dr. James Arnott (from England), described the benefits of local cold application in the treatment of headaches and neuralgia.2 Then, in 1899, Dr. Campbell White first used refrigerants for medical use. He used liquid air to treat a broad range of conditions such as leg ulcers, warts, herpes, and lupus.3

If we skip ahead about 80 years, it is claimed that cryotherapy, as we know it, was pioneered in 1978 by Dr. T. Yamaguchi, a Japanese rheumatologist who treated rheumatoid arthritis patients by freezing the skin’s surface for pain management. He found that a rapid decrease in the skin’s temperature released endorphins that generated numbing and insensitivity to pain.

It is important to note that the information claiming Dr. Yamaguchi as the more recent pioneer of cryotherapy is unreliably sourced from many cryotherapy websites. Interestingly, when I performed various searches on PubMed and Google Scholar for articles relating to “cryotherapy” + “rheumatoid arthritis” with “Yamaguchi” as an author, the search yielded no results.

This is not to say that the information is incorrect; it is just interesting that there were no articles found. Furthermore, “Yamaguchi” was not cited in any of the recent review articles that I read while researching this topic. I would have thought that if Dr. Yamaguchi was a significant pioneer in this field, then his work would be cited at least once.

Nevertheless, based on the literature over the past 20 years, cryotherapy in some form or another has been applied to relieve pain and inflammatory symptoms caused by numerous disorders, particularly those associated with rheumatic conditions.

Health Claims of Cryotherapy

Given its expanding popularity, people can easily now attend cryotherapy sessions in gyms, health spas, and specialized cryotherapy clinics, all of which are cashing in on this health hype.

So what exactly is driving this latest health craze? Briefly, here is a list of health claims collected from multiple cryotherapy clinic websites:

- Reduced inflammation

- Weight loss and removal of cellulite

- Improved sleep quality

- Improved skin and treatment of scar tissue

- Feeling rejuvenated

- Optimized brain function

- Improved immune function

- Increased metabolism

- Injury management

- Increased athletic performance

- Increased collagen production

- Reduced depression and anxiety

It’s amazing that a 1- to 4-minute session in a cryochamber can treat all those conditions simultaneously. Remember, a cryochamber does not discriminate between what conditions it is treating!

It is important to note that none of the cryotherapy clinics that listed these health claims cited any scientific studies in support of these claims.

Time to get serious and look at the scientific evidence.

What Is the Available Research Evidence?

Treatment of Chronic Medical Conditions

A recent (2016) review by Bouzigon et al.4 examined the technologies and health benefits of cryotherapy and reported that there were approximately 30 scientific studies published on this topic prior to 2010, and since then there have been over 100 studies.

In summary, this review reported that WBC and PBC have positive effects on the physical and psychological parameters of Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) patients, and WBC has positive effects on the physical and psychological parameters of patients with Fibromyalgia (FM), Ankylosing Spondylitis (AS), and Multiple Sclerosis (MS).

However, given that some of the health outcomes investigated have very few published studies, it is important to recognize the potential for publication bias, meaning that only studies with positive results are published. In support of this, it is also important to note that, although Bouzigon’s4 review was published in a scientific journal, this research was financially supported by a French cryotherapy company named Cryantal.

Hence, their review article may focus on studies with only positive outcomes. Nevertheless, we can look at these studies and draw our own conclusions.

Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA)

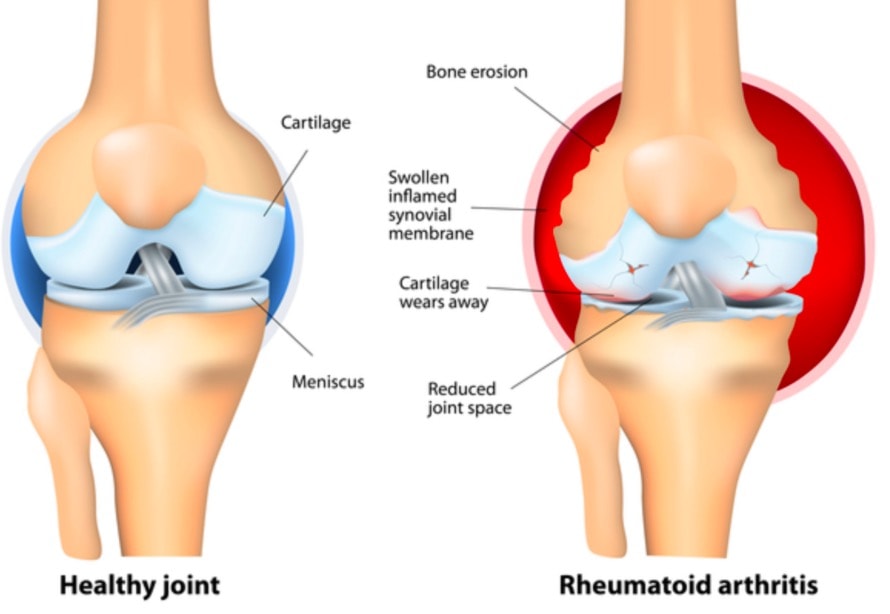

Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) is an autoimmune disorder that primarily affects the joints. Its symptoms include swollen and painful joints.

Bouzigon’s4 recent review cited three studies of the use of WBC on RA patients, where all studies found cryotherapy had a positive (e.g. good) effect on measures of inflammation, pain, disease activity score, fatigue, and morning stiffness. However, it is important to note that these studies had small sample sizes, and thus, a closer look at the results is warranted.

One of the earlier studies reviewed was a randomized, controlled, single-blinded study conducted in Finland by Hirvonen and colleagues,5 which examined the effectiveness of different methods of cryotherapy on pain and inflammation among 60 RA patients. Patients received either WBC at -110°C, WBC at -60°C, application of local cold air at -30°C, or the use of cold packs locally. The patients had 2-3 cryotherapy sessions daily for one week plus conventional physiotherapy.

The results found that, on outcomes measured by the Disease Activity Scores (DAS), the pain seemed to decrease more in patients who received WBC at -110°C than during other cryotherapies, but there were no significant differences in disease activity between the groups. The authors concluded that WBC at -110°C was not superior to local cryotherapy commonly used in RA patients for pain relief and as an adjunct to physiotherapy.

Another study reviewed by Bouzigon4 was conducted in Poland by Gizinska et al.,6 which examined the effect of WBC and traditional rehabilitation on clinical parameters and systemic levels of IL-6, TNF-α in patients with RA. The study was small, with only 25 patients exposed to WBC (−110∘C) and 19 patients undergoing the traditional rehabilitation program.

Results showed that, after therapy, both groups exhibited similar improvement in pain, disease activity, fatigue, time of walking, and the number of steps over a distance of 50m. Overall, the results indicated that WBC was not necessarily better than traditional therapy. Also, improvements in functional status (as assessed by the Health Assessment Questionnaire) were greater among those in the traditional therapy group.

In 2014, a systematic review and meta-analysis pooled together results from 6 studies, which analyzed a total of 257 RA patients.7 Results showed that cryotherapy was associated with a significant decrease in the pain visual analogic scale and 28-joint disease activity score.

The authors concluded that “cryotherapy should be included in RA therapeutic strategies as an adjunct therapy, with potential corticosteroid and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug dose-sparing effects. However, techniques and protocols should be more precisely defined in randomized controlled trials with stronger methodology.”

Another recent study compared two rehabilitation programs on pain, disease activity, locomotor function, and global health in 64 female RA patients.8 All patients underwent individual and instrumental kinesiotherapy and were then divided into two treatment groups (n=32 in each).

Group 1 underwent cryogenic chamber therapy and local cryotherapy, as well as non-weight-bearing, instrumental, and individual kinesiotherapy. Group 2 received traditional rehabilitation in the form of electromagnetic and instrumental therapy, individual and pool-based non-weight-bearing kinesiotherapy.

Rehabilitation lasted 3 weeks and outcomes were examined at three time points: prior to rehabilitation, after 3 weeks of therapy, and 3 months after completing the rehabilitation.

Results showed an improvement in all outcomes (at 3-weeks and 3-months follow-up) among both groups; however, these improvements were greater in the group who received cryotherapy (Group 1) than the traditional rehabilitation group (Group 2).

Bottom Line

Based on the current literature, there is plausible evidence that cryotherapy reduces pain and inflammation among RA patients. However, there still need to be further large-scaled well-designed studies to confirm these findings.

Multiple Sclerosis (MS)

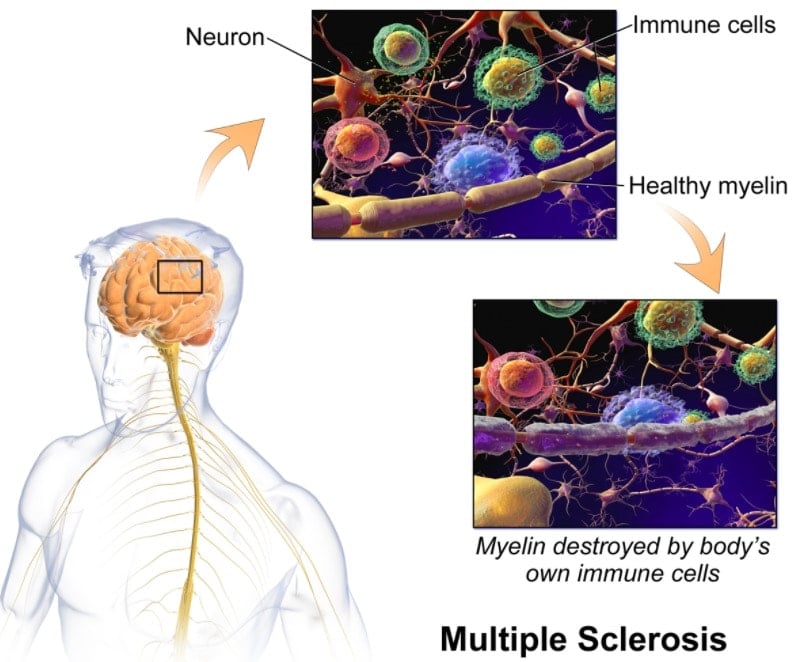

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a condition of the central nervous system, interfering with nerve impulses within the brain, spinal cord, and optic nerves. MS involves a variety of symptoms, including muscular spasms, weakness coordination and balance problems, neurological and psychological symptoms, and fatigue.

The Bouzigon4 review cited three studies investigating the use of cryotherapy among MS patients and reported that cryotherapy has a positive (e.g. good) effect on spinal mobility, fatigue, and functionality, and leads to an increase in uric acid. It is important to note that these three studies were all published by the same group of researchers in Poland (Miller and colleagues).

Hence, it is interesting to question why other researchers throughout the world haven’t investigated this topic in more detail. Nevertheless, let’s take a closer look at these studies.

The most recent study by Miller and colleagues9 examined WBC on fatigue and functional and psychological status in MS patients with low (LF group, n=24) and high (HF group, n=24) levels of fatigue. Study participants in each group were exposed to ten 3-minute sessions of WBC (one exposure per day at -110°C or lower).

Functional status was measured by Rivermead Moor Assessment (RMA), Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS), MS Impact Scale (MSIS-29), which includes two sub-scales of physical and psychological status. Results showed that, in both groups, the WBC sessions induced a significant improvement in the functional status and self-reported fatigue.

The observed changes were significantly greater in the HF group than in the LF group. However, the authors state that “one limit in our study concerns the lack of information on how long the effects (concerning fatigue and other measured variables) are maintained after WBC.

In their earlier study, Miller and colleagues10 investigated whether WBC is associated with changes in total antioxidative status (TAS), as it has been suggested that MS is not only characterized by immune-mediated inflammatory reactions but also by neurodegenerative processes. They recruited 32 MS patients into two groups: 16 patients exposed to 10 daily treatments of WBC [2-3 min], and 16 patients in a control group treated with a program of exercises, as well as a group of 20 healthy subjects.

Results showed that the level of TAS in MS patients was significantly reduced compared to healthy subjects. The authors concluded, “our results suggest positive antioxidant effects of WBC as a short-term adjuvant treatment for patients suffered due to MS.”

A study published in 2002 investigated changes in uric acid levels associated with exposure to WBC.11 Uric acid is suggested to be a marker of MS activity, where lower uric acid levels in MS patients are associated with relapse. Therefore, the purpose of the study was to see if WBC increased uric acid levels in MS patients. The study recruited 22 MS patients and 22 healthy controls and administered the same WBC exposure protocol as described above.

They collected results before the WBC treatment and at one and three months after post-treatment. The results found that WBC significantly increased plasma uric acid levels after the 10 WBC sessions at one-month and three-months follow-up. The authors concluded that WBC may be used as adjuvant therapy via increased uric acid blood level.

Despite the purported benefits of WBC for MS patients, it is interesting to note that WBC is not endorsed by any official international MS organizations. An examination of major MS websites showed that cryotherapy is not mentioned, let alone endorsed as a viable complementary therapy, on any of the MS Australia (https://www.msaustralia.org.au), National MS Society (https://www.nationalmssociety.org), and MS Foundation (https://msfocus.org) websites.

Bottom Line

While results from only a handful of studies (all of which were conducted by the same group of researchers) suggest that WBC may help improve MS, it is still very early days and far more research is warranted before these health claims of WBC are even plausible.

Fibromyalgia (FM)

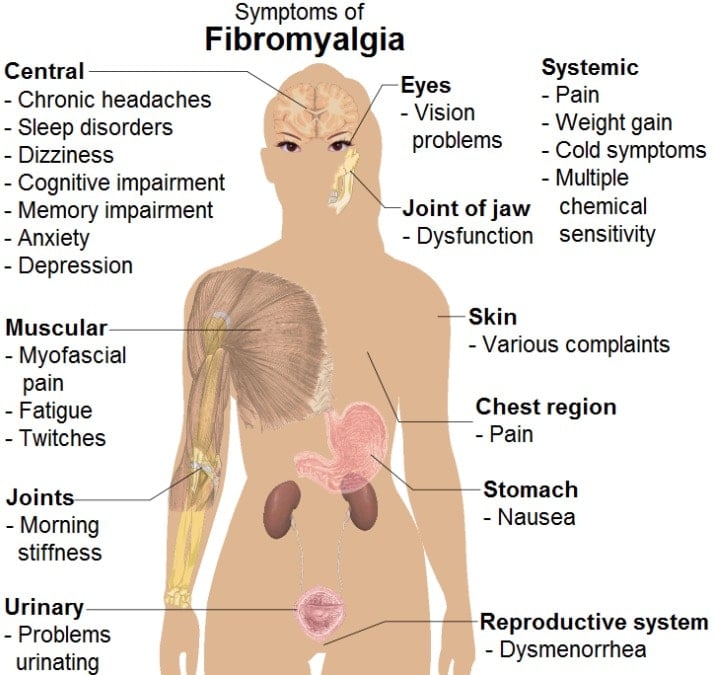

Fibromyalgia is a chronic condition that causes pain in the muscles and bones. Other common symptoms are lethargy and poor sleep.

Bouzigon’s4 review reported only one study regarding FM patients.12 The study recruited 100 FM patients (aged 17-70 years), with a group of 50 subjects exposed to WBC (15 sessions over a period of 3 weeks) and 50 subjects in a control group with no WBC. All subjects maintained their prescribed pharmacological therapy during the study (analgesic and antioxidants).

The health status of the subjects was examined (pre- and post-observation) with the Visual Analogue Scale, Short Form-36, Global Health Status, and Fatigue Severity Scale. Results showed a positive effect of WBC with improvements in all the quality of life indexes. However, the authors speculated that “... this improvement is due to the known direct effect of cryotherapy on the balance between pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators having a recognized role in the modulation of pain.”

Bottom Line

Simply not enough evidence to claim that WBC improves the quality of life among FM patients.

Ankylosing Spondylitis (AS)

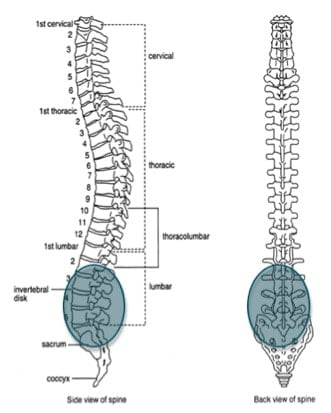

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is a type of inflammatory arthritis that targets the joints of the spine. It first affects the sacroiliac joint, where the spine attaches to the pelvis. The hips and shoulders can be affected, as can the eyes, skin, bowel, and lungs. Symptoms of AS include back pain, stiffness, and reduced mobility in the spine.

Bouzigon’s4 review reported only one study of WBC among AS patients.13 The study investigated whether WBC could potentially have more beneficial effects than regular kinesiotherapy procedures alone. Outcomes were assessed on a range of standardized clinical measures of pain, fatigue, mobility, and functionality from the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Diseases Activity Index (BASDAI) and the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI).

The study comprised 48 AS patients assigned to two groups: Group 1) exposed to WBC (3 minutes a day) followed by 60 minutes of kinesiotherapy (n=32); or Group 2) 60 minutes of kinesiotherapy only (n=16). The study period was 10 consecutive days (excluding weekend).

Results showed that the BASDAI index scores decreased about 40% in Group 1 (WBC + kinesiotherapy) compared to a decrease of about 15% in Group 2 (kinesiotherapy only). Similarly, the BASFI index decreased about 30% in Group 1 (WBC + kinesiotherapy) and decreased only about 16% in Group 2 (kinesiotherapy only).

The authors concluded that WBC procedures may have some beneficial influence on AS patients through a decrease of the BASDAI and BASFI index, pain intensity, and improvement of some spinal mobility parameters.

Major limitations of this study were 1) the small sample size and 2) the study did not provide long-term follow-up (e.g. 3 months), and therefore it is unknown how long the effect of WBC was maintained.

Bottom Line

One small study is not enough evidence to claim that WBC improves the quality of life among AS patients.

Muscle Recovery From Soreness

WBC treatment is becoming popular among athletes as a method of relieving muscle soreness for a faster recovery. In 2014, Bleakley and colleagues14 published a review article assessing the efficacy and effectiveness of WBC among athletes. The authors focused on the empirical evidence from controlled trials and examined the biochemical, physiological, and clinical effects of WBC. After analyzing data from 10 relevant controlled studies (of which the majority were based on small numbers), the authors found only weak evidence that WBC enhanced the biophysiological mechanisms relevant to sports recovery. Overall, they concluded that there was very little evidence to support WBC having a positive effect on muscle soreness and functional recovery and stated that:

“Controlled studies suggest that WBC could have a positive influence on inflammatory mediators, antioxidant capacity, and autonomic function during sporting recovery; however, these findings are preliminary. Although there is some evidence that WBC improves the perception of recovery and soreness after various sports and exercise, this does not seem to translate into enhanced functional recovery.”

Following this review, a comprehensive “gold standard” Cochrane systematic literature review was conducted in 2015 by Costello and colleagues.15 The review assessed the effects (benefits and harms) of WBC for preventing and treating muscle soreness after exercise in adults and focused on randomized trials comparing different durations or dosages of WBC with primary outcomes being muscle soreness, subjective recovery (e.g. tiredness, well-being), and adverse effects.

Only four laboratory-based randomized controlled trials passed the selection criteria and were included in the final analyses, which contained results for a total of 64 physically active, predominantly young adult males. All four studies compared WBC with either passive rest or no treatment. Results of the pooled analysis provided some evidence that WBC may reduce muscle soreness (pain at rest) at 1, 24, 48, and 72 hours after exercise.

However, the evidence also included the “possibility that WBC may not make a difference or may even make the pain worse.” The authors further concluded that “the currently available evidence is insufficient to support the use of WBC for preventing and treating muscle soreness after exercise in adults.” They also erred on the side of caution stating that “…the best prescription of WBC and its safety are not known.”

Bottom Line

Based on the two review articles, there is limited, or weak, evidence suggesting that WBC assists in the recovery of muscle soreness after exercise. There was weak evidence that WBC reduces inflammation.

Does Cryotherapy Assist in Weight Loss?

On the face of it, this idea is plausible theoretically. It is suggested that when exposed to colder temperatures, your body has to work harder to maintain a normal body temperature and, therefore, uses more calories to do so. In general, humans have two main types of body fat, white adipose tissue (WAT) and brown adipose tissue (BAT). WAT’s main role is lipid storage, and it undergoes pathological expansion as we put on weight, which can further lead to obesity.

On the other hand, BAT’s primary function is thermoregulation, and it produces heat by non-shivering thermogenesis, therefore contributing to whole-body energy expenditure. Because of BAT’s energy dissipating activity, there is an inverse relationship between BAT and body fatness, hence BAT may play a protective role against body fat accumulation.16

It is hypothesized that an increase in BAT helps reduce body fat, and one way of increasing BAT is through exposure to cold temperatures.17 Several studies have reported results that support this hypothesis.

One of these studies18 recruited 22 subjects with low or undetectable activities of BAT, and randomly divided them into 2 groups: 1) exposed to cold at 17°C for 2 hours every day for 6 weeks (n = 12); and 2) a control group that maintained their usual lifestyles without cold exposure during the same period (control group; n = 10).

Body fat content and energy expenditure at 27°C and after 2-hour cold exposure at 19°C were measured before and after the 6-week period. Results showed that “human BAT can be recruited by chronic cold exposure and capsinoid ingestion even in individuals who have lost active BAT. Our findings could contribute to developing practical, easy, and effective anti-obesity regimens.”

However, given its potential role in stimulating energy expenditure, BAT activation has become a trending topic as an anti-obesity treatment. A recent review of the current evidence on this topic by Marlatt and Raussin19 pointed out that most studies on BAT stimulation have been conducted in rodents and used cold stimulation. Furthermore, to date, very few human trials test the effect of cold exposure on BAT.

The authors also stated that the studies showed that BAT’s contribution to overall energy metabolism was insufficient to cause weight loss. They concluded by stating, “there is no convincing evidence yet to indicate that BAT may be a viable pharmaceutical target for body weight loss or even weight loss maintenance.”

It is also very important to note that, although there has been a handful of BAT stimulation studies, none of these studies used cryotherapy as a method of exposure, and they did not focus on “weight loss” as a primary outcome. Furthermore, a detailed search of PubMed and Google Scholar with various combinations of search terms for “cryotherapy” and “weight loss” yielded no results. This suggests that there is absolutely no scientific evidence that cryotherapy assists in weight loss.

While there were no specific studies on WBC and weight loss, the only studies found that were of any slight relevance to losing weight in cold temperatures were conducted in the early 1980s among only a handful of participants. A study published in 1982 examined whether exercising in cool water could help you lose more weight.20

The study was among seven obese women who performed moderate exercise in cool water (17 to 22 degrees C) five times per week for eight weeks to determine if cold exposure and the attendant caloric deficit in body heat stores would lead to body weight loss. Results showed that “while cold exposure does not increase caloric expenditure significantly in obese individuals, exercising regularly in cool water may be beneficial as it may motivate obese people to exercise at higher intensity for thermal comfort and the water environment may help prevent injuries.”

Another study in 198421 investigated body insulation levels in seven healthy male subjects during rest and exercise for 3-hour periods in cool water. They found that “as a practical consequence, heat generated by muscular exercise in water colder than critical water temperature cannot offset cooling unless the exercise intensity is great.”

Bottom Line

This claim that cryotherapy can promote weight loss is nothing but a false marketing ploy. There is no evidence that cryotherapy helps you lose weight. Totally ignore this ridiculous claim. Although it has been suggested that exposure to cold temperatures increases brown adipose tissue, which may increase energy expenditure, there is no evidence that you can lose weight from exposure to WBC.

Does Cryotherapy Slow Down Ageing?

It has been suggested that a low body temperature may extend longevity by affecting metabolic rates by decreasing the rate of biochemical reactions, and thus retarding whatever process(es) which cause ageing.22 This theory, however, is largely based on animal studies. No doubt the cryotherapy health craze has used this “anti-ageing” concept as part of its marketing campaign, but there are no studies assessing the relationship between WBC and the ageing process.

In real terms, it is also very difficult to conduct individual-level epidemiological studies on exposures to ambient temperatures (or long-term exposures to cold temperatures in a controlled environment) to accurately assess anti-ageing, or even age-related mortality. A simple method would be to compare the age-related mortality rates across countries that experience varying levels of temperature to see if people in colder temperatures live longer; however, the single effect of temperature on ageing could not be teased out from the many other contributing factors.

Furthermore, in this context, how do you even define the term “slowing down of the ageing process,” as it can refer to the body internally, externally, or overall general health and fitness? Generally, we could say that people assess the slowing down of the ageing process esthetically, meaning that if your appearance (e.g. mostly skin) looks “younger than your age,” then people say you have aged well.

One way of looking younger is to avoid/eliminate facial wrinkles. A new non-invasive treatment called “focused cold therapy (FCT)” (also known as cryoneuromodulation) uses highly pressurized nitrous oxide to improve the appearance of fine lines and facial wrinkles. Although this is not WBC, it warranted a mention in order to get the WBC advocates excited. However, there is also very little research on FCT and anti-ageing. One study of 41 subjects reported that FCT on forehead wrinkles made a “significant clinical improvement with high subject satisfaction.”23

Bottom Line

This claim that cryotherapy slows down the ageing process is nothing but a false marketing ploy. There is absolutely no evidence to suggest that exposure to WBC reduces ageing or has any impact on the ageing process.

Does Cryotherapy Improve Mental Health?

In the recent review article by Bouzigon et al.,4 there was only one study cited that specifically investigated the effect of WBC on mental health symptoms (depression and anxiety).24 The study comprised 60 participants with depressive and anxiety disorders (ICD-10 criteria) who were being treated at an outpatient psychiatric clinic.

The subjects were assigned to either a control group (n=34) or a study group (n=26) who were treated using a cycle of 15 visits to a cryogenic chamber carried out daily from Monday to Friday. The subjects in both groups received standard psychopharmacotherapy as prescribed by their psychiatrists. The primary outcomes included standardized clinical measures of depression and anxiety, which were recorded at baseline and weekly for a period of 3 weeks.

Results showed a significant improvement in symptoms, with a decrease of at least 50% from the baseline severity of symptoms, which was observed in almost half of the study group and only in one case in the control group. The authors concluded that their findings, despite such limitations as a small sample size, suggested a possible role for WBC as a short-term adjuvant treatment for mood and anxiety disorders.

Bottom Line

Given the results of this one small study, there is no evidence that cryotherapy improves mental health symptoms. Cryotherapy should not be considered as a primary treatment for mental health disorders.

Does WBC Boost Collagen?

Collagen is the main structural protein in our bodies largely found in skin (and scar tissue), tendons, cartilage, blood vessels, and bones. There are many “collagen-boosting” products on the market that claim to improve and maintain healthy skin. Now there are claims that WBC boosts collagen to give you a healthy, glowing skin.

Although spray-type cryotherapy (e.g. cryosurgery) is used to treat scar tissue and remove warts, skin tags, and benign skin cancers, etc., there is no research focusing on WBC as a collagen booster.

Bottom Line

This claim is false. There is no evidence that WBC increases collagen.

Is Cryotherapy Safe?

A recent review of the available medical literature on the safety and efficacy of WBC by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)25 concluded that the evidence was lacking and also raised concerns about the safety of WBC. Dr. Yustein of the FDA reported that: “We found very little evidence about its safety or effectiveness (of WBC) in treating the conditions for which it is being promoted.”

Furthermore, the FDA reported that:

There is an increased risk of asphyxiation when liquid nitrogen is used for cooling. The addition of nitrogen vapors to a closed room lowers the amount of oxygen in the room and can result in hypoxia (oxygen deficiency), which can lead to loss of consciousness. In addition to hypoxia, other risks include frostbite, burns, and eye injury from the extreme temperatures.

To date, there has been one reported death associated with WBC.26 A 24-year-old woman was found dead in a cryochamber facility in Las Vegas. The woman, who was an employee of the facility, had reportedly entered the chamber alone and without supervision and froze to death within minutes.

Bottom Line

WBC is not endorsed by official health authorities, and it can be potentially dangerous, especially if used without supervision, or by untrained operators. The use of WBC cryochambers is not regulated, which also poses a safety concern.

Conclusion

Scientific vs. Anecdotal Evidence, and Future Research

Various forms of cryotherapy (e.g. cryosurgery and localized) are used in clinical settings for various conditions, such as the treatment of skin conditions (e.g. removal of warts, skin tags, benign cancer, etc.) and relieving localized pain in muscles and joints in patients with chronic conditions. Given the enticing health claims of WBC, cryotherapy clinics have become big business.

Unfortunately, once the crowd-momentum of a trend starts, it is often difficult to debunk popular beliefs. Therefore, people often rely on societal beliefs from marketing trends and anecdotal evidence way before relying on scientific evidence. Furthermore, how often do members of the public perform their own literature reviews on the current scientific evidence before purchasing novel health treatments?

Based on the current scientific literature, there is very little evidence (if any) that supports the health claims of WBC marketed by cryotherapy clinics. While there has mostly been “clinical” research on patients with chronic conditions (e.g. RA, FM, MS), and research focusing on the enhanced recovery of athletes, these research findings have been exploited by cryotherapy clinics and marketed to the public in a way far beyond the original purpose of the research.

This means that treatments researched for medical conditions are marketed to “healthy” people who do not have these conditions as a form of maintaining their health, when in fact these “healthy” people do not require WBC at all, as there is no proven ability for it to maintain or enhance their health.

No doubt, further research is required to corroborate the limited positive findings reported within the current scientific literature. Future research needs to first build on the current evidence and focus on the use of WBC to treat muscle and joint pain in patients with chronic conditions, and potentially muscle recovery among athletes.

Two major limitations of the current research that need to be improved are:

- Small sample sizes

- Investigation of longer-term treatments and longitudinal studies that follow participants over time to assess the long-term benefits of WBC.

As for research regarding the more novel health claims of WBC, such as weight loss, anti-ageing, and mental health, it is highly unlikely that quality research would be funded.

Thus, the public will always rely on anecdotal evidence and marketing surrounding these claims.

Lastly, keep in mind that well-designed large-scale research studies that recruit human participants are very timely and costly, so there needs to be strong interest from researchers and large financial funding bodies for there to be any potential of quality research in this area. Unfortunately, the business world of cryotherapy clinic franchises (that are popping up everywhere) moves at a much faster pace than quality science.

Final Bottom Line

While there is potential for WBC to be further researched as a method of relieving muscle soreness and joint pain in patients with chronic medical conditions, there is absolutely no evidence that supports the remaining health claims marketed by cryotherapy clinics, such as weight loss, anti-ageing, depression and anxiety, and collagen boosting.

WBC should be seen as a novel and “fun” experience, and should not be considered as a treatment for weight loss, anti-ageing, mental health conditions, or enhanced athletic performance, as there are other well-proven treatments for these conditions.

Leave a Reply